https://www.kit.org/walking-the-path/intersectionality-type-of-discrimination-word-cloud/

https://www.kit.org/walking-the-path/intersectionality-type-of-discrimination-word-cloud/

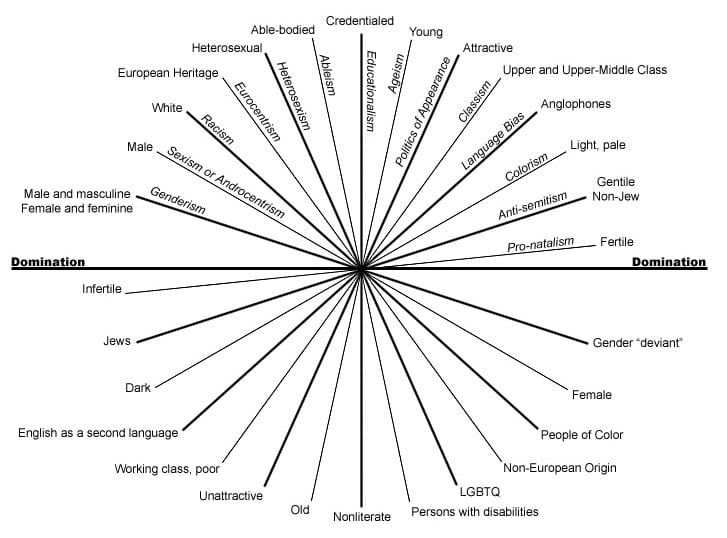

Intersectionality is directly correlated to all types of oppression. Oppression is described as the force that allows, through the power of norms and systems, the unjust treatment or control of people. Intersectionality shows us that social identities work on multiple levels, resulting in unique experiences, opportunities, and barriers for each person It is the study of overlapping or intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination. Some of the aspects that are considered are biological, social and cultural categories such as gender, race, class, ability, sexual orientation, religion, caste, age, nationality and other sectarian axes of identity interact on multiple and often simultaneous level. The ecofeminist intersectionality movement brings together notions of feminism and environmentalism in order to find effective solutions against all types of oppressive behaviors …

There are three main aspects to intersectionality theory that should be considered.

1. Intersectionality theory viewed at the micro or individual level, i

This is a way to help identify people are where they may be oppressed by category. The diagram below helps to clarify this theory. People are very likely to be both an oppressor and the oppressed based on their individual and unique characteristics and circumstances.

2. Intersectionality is also a framework for analysis. This takes a more generic approach to analyzing intersectionality. Some of the categories would be race, financial status, marriage, sexual orientation as well as media stereotypes which help to influence public opinion.

In “The Ecology of Feminist and the Feminism of Ecology” (1989), Ynestra King states that ecofeminist principles are based on the following beliefs:

The survival of the species necessitates a renewed understanding of our relationship to nature, of our own bodily nature and of nonhuman nature around us; it necessitates a challenging of the nature-culture dualism and a corresponding radical restructuring of human society according to feminist and ecological principles. Adrienne Rich says, “When we speak of transformation we speak more accurately out of the vision of a process which will leave neither surfaces nor depths unchanged, which enters society at the most essential level of the subjugation of women and nature by men…” (470-471).

Kings, A.E. “Intersectionality and the Changing Face of Ecofeminism.” Ethics & the Environment, vol. 22 no. 1, 2017, p. 63-87. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/660551.

Kimberlé Crenshaw: The urgency of intersectionality | TED Talk

Intersectional research broadly falls into three main categories: theory, methodology, and application. Each category tends to grapple with one central question, respectively: What is intersectionality? How do we use intersectionality? And what does intersectional research demonstrate? While the term “intersectionality” originally originated in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it did not gain traction and finally acceptance for many years before Crenshaw first explicitly defined it in 1989. Ecological feminism or ecofeminism is an area of study concerned with understanding the interconnected relationship between the domination of women and the domination of nature. For over thirty years, ecofeminism has been taking into account the interconnected nature of social categories such as gender, race, class, sexuality, caste, species, religion, nationality, dis/ability, and issues such as colonialism. It has also challenged anthropocentric modes of thought, by incorporating both species and the natural environment into the ongoing debate concerning the workings of social categorization and identity construction. However, we need to be careful in characterizing earlier ecofeminist work as intersectional. Although it is certainly true that ecofeminism did often engage with intersectional approaches, it did not adopt intersectionality as the conceptual tool we currently understand it to be.

“Ecofeminism exposes the repression of women and the environment as interlinked and rooted in patriarchal structures.” https://www.thegoodtrade.com/features/ecofeminism-intersectional-environmentalism-difference/

Both Ecofeminism and Intersectional Environmentalism explore how the treatment and degradation of the earth exposes a deeply rooted societal problem. But while Ecofeminism narrows in on gender, sexuality, and the patriarchy, Intersectional Environmentalism creates space for all social injustices, including sexism.

“I am ??????? ” The Complexity of Identity: “Who Am I?” Beverly Daniel Tatum

UNDERSEA I Who has known the ocean? Neither you nor I, with our earth-bound senses, know the foam and surge of the tide that beats over the crab hiding under the seaweed of his tide pool home; or the lilt of the long, slow swells of mid-ocean, where shoals of wandering fish prey and are preyed upon, and the dolphin breaks the waves to breathe the upper atmosphere. Nor can we know the vicissitudes of life on the ocean floor, where the sunlight, filtering through a hundred feet of water, makes but a fleeting, bluish twilight, in which dwell sponge and mollusk and starfish and coral, where swarms of diminutive fish twinkle through the dusk like a silver rain of meteors, and eels lie in wait…..

Rachel Louise Carson (1937). Undersea. Atlantic Monthly, 78:55–67

The Pando Forest, Utah

The Trembling Giant, or Pando, is an enormous grove of quaking aspens that take the “forest as a single organism” metaphor and makes it literal: the grove really is a single organism. Each of the approximately 47,000 or so trees in the grove is genetically identical and all the trees share a single root system. While many trees spread through flowering and sexual reproduction, quaking aspens usually reproduce asexually, by sprouting new trees from the expansive lateral root of the parent. The individual trees aren’t individuals but stems of a massive single clone, and this clone is truly massive. This ecological treasure is a metaphor for human environmental intersectionality. “Pando” is a Latin word that translates to “I spread.”Pando, the Trembling Giant – Richfield, Utah – Atlas Obscura

Hi Catherine, I really enjoyed reading your post and it was super easy to follow as well. In the beginning of your post you stated “People are very likely to be both an oppressor and the oppressed based on their individual and unique characteristics and circumstances.” I think this is a very important point, and it brought me back to Kings article where she is writing about Matsuda’s asking the other question mentality. She states, “Reflecting upon one’s position, especially when speaking from a point of privilege, helps to avoid the unintentional marginalization of other groups or identities” (King, page 64). Being able to check your own privilege and recognize that one be both oppressed and an oppressor is crucial to enact any change. Being able to admit to being both is also contributing the intersectional analyses of society because it is acknowledging different identities and how those identities play into our system and how they may effect other people, which would lead to acknowledging how many different ways the environment is oppressed based on the identity (or use) we are giving it at the time of its oppression.